This article is part one, of a two part discussion, on Identifying Bad Actors for private placements.

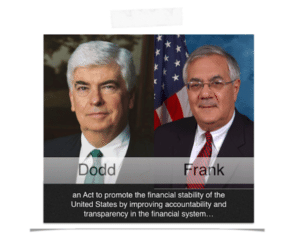

In 2010, as part of the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, Congress adopted the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. While most of the Act addressed the financial services industry, one significant provision targeted perceived risks in private capital markets, including capital raising by private companies and private funds. The Act required the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to adopt rules banning specified felons and other “bad actors” from participating in private offerings of securities under Rule 506 of Regulation D under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended. The SEC fulfilled its mandate by adopting Rule 506(d) in 2013. As discussed below, this rule effectively requires a company to investigate the background of its officers, directors, owners and other associates before using Rule 506 – the most powerful capital-raising tool available to private companies and private investment funds.

Part I of this series will take a broad look at the background, purpose and scope of Rule 506(d) to explain why bad actor due diligence is becoming a necessary component of any well managed private capital raise and to outline the types of misconduct for which issuers must be vigilant in selecting business associates. Part II will focus on the specifics of the bad actor rule and outline a phased approach to due diligence that exercises reasonable care in investigating for past bad acts while avoiding excess effort and expense.

Part I of this series will take a broad look at the background, purpose and scope of Rule 506(d) to explain why bad actor due diligence is becoming a necessary component of any well managed private capital raise and to outline the types of misconduct for which issuers must be vigilant in selecting business associates. Part II will focus on the specifics of the bad actor rule and outline a phased approach to due diligence that exercises reasonable care in investigating for past bad acts while avoiding excess effort and expense.

Why Rule 506?

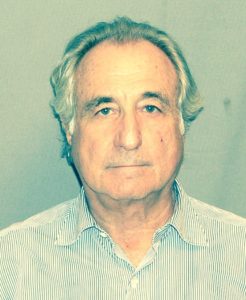

Why did Congress single out Rule 506 offerings as an activity where felons and other wrongdoers must be identified and banned? It did so because Rule 506 offerings represent approximately one trillion dollars per year of largely unregulated financial transactions, and Rule 506 is the fundraising tool of choice for private issuers and funds, including hedge funds, private equity funds and other pooled funds. The collapse of the private funds managed by Bernard L. Madoff, which prosecutors estimated to involve a $65 billion fraud, revealed that even ostensibly sophisticated investors could fail to identify fictitious investments on a scale large enough to damage the national economy and destroy the personal finances of many.

Why did Congress single out Rule 506 offerings as an activity where felons and other wrongdoers must be identified and banned? It did so because Rule 506 offerings represent approximately one trillion dollars per year of largely unregulated financial transactions, and Rule 506 is the fundraising tool of choice for private issuers and funds, including hedge funds, private equity funds and other pooled funds. The collapse of the private funds managed by Bernard L. Madoff, which prosecutors estimated to involve a $65 billion fraud, revealed that even ostensibly sophisticated investors could fail to identify fictitious investments on a scale large enough to damage the national economy and destroy the personal finances of many.  While the “bad actor” rules themselves would have done nothing to stop the Madoff fraud, new Rule 506(d) stands for the proposition that even wealthy and sophisticated investors are entitled to an assumption that persons legally offering them securities are not convicted felons or persons who have been cast out of the more regulated sectors of the financial community for their misdeeds.

While the “bad actor” rules themselves would have done nothing to stop the Madoff fraud, new Rule 506(d) stands for the proposition that even wealthy and sophisticated investors are entitled to an assumption that persons legally offering them securities are not convicted felons or persons who have been cast out of the more regulated sectors of the financial community for their misdeeds.

Rule 506 is a safe harbor under the Securities Act that allows issuers to sell an unlimited amount of securities to an unlimited number of “accredited investors” – investors who theoretically have the sophistication or financial resources to invest wisely and withstand losses – without registering the securities with the SEC. Absence of registration means that the company selling securities to raise capital, known as the “issuer,” can avoid the time, expense and management distraction of clearing a prospectus with the SEC, an intimidating process most often associated with a company “going public” in an IPO. In addition, an issuer that raises funds under Rule 506 – even tens or hundreds of millions of dollars –can also remain private and avoid the reporting and compliance burdens of becoming a public company as long as it, in most cases, does not have more than 2000 accredited investors as record holders. Moreover, since 1996, state securities agencies have generally had no authority to regulate offerings under Rule 506. As a result, Rule 506 offerings are not reviewed by any agency and are seldom investigated. Beyond businesses seeking capital for growth, private funds such as private equity funds, hedge funds and venture capital funds have increasingly relied on Rule 506 to raise capital.

Both the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act of 2012 are reactions to the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath. While the authors of Dodd Frank sought to restrain abuses that they perceived as having created the crisis, the authors of the JOBS Act attempted to address the crisis’ lingering economic stagnation by loosening restraints on private capital formation. Both laws aimed changes at Rule 506 because of its central place in private capital markets and the enormous dollar volume of securities sold under the rule.

The Importance of Due Diligence

The Bad Actor Disqualifications under Rule 506(d) make Rule 506 unavailable if an issuer or specified “covered persons” committed any of the bad acts listed in Rule 506(d). A private offering that claims reliance on Rule 506, but involves a disqualified issuer or individuals, may be an illegal offering in violation of Section 5 of the Securities Act, which can lead to civil and criminal penalties that include fines and prison unless some other exemption from registration can be found to cover the offering. In particular, when an offering is advertised through a “general solicitation” as permitted under Rule 506(c) adopted under the JOBS Act, where no other exemption would be available, disqualification will make the offering an illegal public offering. In that instance, the issuer’s officers and directors can face harsh penalties under the Securities Act even if no fraud has actually occurred.

The Bad Actor Disqualifications under Rule 506(d) make Rule 506 unavailable if an issuer or specified “covered persons” committed any of the bad acts listed in Rule 506(d). A private offering that claims reliance on Rule 506, but involves a disqualified issuer or individuals, may be an illegal offering in violation of Section 5 of the Securities Act, which can lead to civil and criminal penalties that include fines and prison unless some other exemption from registration can be found to cover the offering. In particular, when an offering is advertised through a “general solicitation” as permitted under Rule 506(c) adopted under the JOBS Act, where no other exemption would be available, disqualification will make the offering an illegal public offering. In that instance, the issuer’s officers and directors can face harsh penalties under the Securities Act even if no fraud has actually occurred.

The disqualifying acts under Rule 506(d) generally include criminal convictions and court orders involving securities, disciplinary actions by state or federal securities regulators or by banking or insurance regulators, expulsion from membership in a securities exchange or a national securities association for failing to follow just and equitable principles of trade and mail fraud.

The disqualifying acts under Rule 506(d) generally include criminal convictions and court orders involving securities, disciplinary actions by state or federal securities regulators or by banking or insurance regulators, expulsion from membership in a securities exchange or a national securities association for failing to follow just and equitable principles of trade and mail fraud.

An issuer that embarks on a Rule 506 offering that has – even unknowingly – engaged a bad actor as an officer or director, has a bad actor directly or indirectly owning a large amount of shares or engages a bad actor to solicit investors, could embroil the company and otherwise blameless officers and directors in the criminal enterprise of an illegal securities offering. The last line of defense that can shield the company and its good actors from liability – and restore the availability of Rule 506 – is to show that the issuer did not know of the disqualification and, in the exercise of reasonable care, could not have known that a disqualification existed.

The emphasized words in the preceding sentence create a “due diligence” defense that not only shields from liability but affirms the exempt, legal nature of the offering. Those words also create a due diligence obligation for any company that is not cavalier about the prospect of fines, prison and devastating publicity. It is not enough for a company and its managers to be unaware of a bad actor in their midst. They must exercise reasonable care, i.e. conduct a reasonable investigation to discover if any covered person is a bad actor.

What is a reasonable investigation? The rule itself offers only the following guidance in an instruction:

“An issuer will not be able to establish that it has exercised reasonable care unless it has made, in light of the circumstances, factual inquiry into whether any disqualifications exist. The nature and scope of the factual inquiry will vary based on the facts and circumstances concerning, among other things, the issuer and the other offering participants”.

While Rule 506 is considered a “safe harbor,” the quoted guidance leaves the issuer in the unsheltered waters of “facts and circumstances,” without an indication of what steps constitute an insufficient inquiry or how far an inquiry must go before it is unnecessarily expensive or intrusive. Further guidance may eventually come in the form of court decisions or settlements of enforcement actions, but none is available now.

While Rule 506 is considered a “safe harbor,” the quoted guidance leaves the issuer in the unsheltered waters of “facts and circumstances,” without an indication of what steps constitute an insufficient inquiry or how far an inquiry must go before it is unnecessarily expensive or intrusive. Further guidance may eventually come in the form of court decisions or settlements of enforcement actions, but none is available now.

In the view of many practitioners, the minimum requirement for a reasonable inquiry under Rule 506(d) is to identify all covered persons, to ask them if they have committed any of the bad acts specified in the rule and to conduct a background check that includes all publicly available records that would report or publish the convictions, orders, judgments, decrees, suspensions, expulsions or bars that comprise the bad acts. Such a background check should also follow up with greater scrutiny any “red flag” indicating possible bad acts that appears in threshold research. Certainly, an inquiry that failed to discover bad acts that appear on a covered person’s “Google” search will be found inadequate if nothing else is undertaken. In addition, if a company conducts background checks for its own protection (or to comply with the Sarbanes Oxley Act requirements) it must exercise the same level of diligence in investigating covered persons before a Rule 506 offering to establish the reasonableness of the inquiry.

Bad actor due diligence is not necessarily a one-time thing. Issuers that engage in multiple offerings, like private funds that may be almost continuously engaged in Rule 506 offerings, must exercise continuing diligence to confirm that a covered person who was previously cleared has not been disqualified by a subsequent act or a court or administrative ruling. Contracts with financial advisors and other providers who are potentially covered persons should include an obligation to report the occurrence of any bad act to the issuer and an agreement to provide certifications of the absence of bad acts and bad actors on request.

Grandfathering

In its final rules under Rule 506(d), the SEC provided that a bad actor whose conviction, order, judgment, decree, suspension, expulsion or bar occurred prior to September 23, 2013, when the rules became effective, will not be disqualified; rather, the issuer must notify all purchasers of securities of the bad acts a reasonable time before the sale. Some refer to this relief from exclusion – which would allow even a felon convicted of securities fraud to participate in a Rule 506 offering – as “grandfathering.” The notice requirement is subject to the identical due diligence standard that applies to disqualification. Failure to disclose prior bad acts under the rule will also result in a loss of the exemption under Rule 506, with the same potential for civil or criminal liability.

Conclusion

Part I of this series should have persuaded the reader of the importance of developing a sound due diligence plan before raising money under Rule 506. In developing a plan, it is useful to keep in mind that neither Congress nor the SEC intended to regulate Rule 506 out of existence and that an exhaustive, prohibitively expensive investigation should not be necessary. Part II of this series will dig more deeply into the specifics of Rule 506(d) and lay out a practical approach to bad actor due diligence.

Jor Law is a co-founder of Homeier & Law, P.C., where he practices corporate and securities law, including helping companies take advantage of alternative forms of capital raising such as Regulation D, Rule 506(c) offerings and crowdfunding. He is also a co-founder of VerifyInvestor.com, the resource for accredited investor verifications trusted by broker-dealers, law firms, companies, and investors who insist on safety and reliability.

Charles Kaufman, Counsel at Homeier & Law P.C., has been advising growing companies and their leaders for 20 years. In private law firms and as general counsel of a public company he has helped his clients to create, finance, govern, combine and exit their businesses, and to form strategic alliances, across a broad range of industries, including medical devices, healthcare, software, nanotechnology, film and music production, garment manufacturing, retailing, real estate investment and semiconductors. Charles advises early stage companies on obtaining both debt and equity capital from angel and venture capital investors, as well as expanded opportunities under Regulation 506(c) and the proposed crowdfunding rules of the JOBS Act. He has extensive experience advising public companies on securities regulation and compliance and advising both new and established companies in public and private securities offerings during a period of rapid change in the financial and regulatory landscape, from the still-emerging JOBS Act to Dodd-Frank and Sarbanes-Oxley. Charles earned both his J.D. and B.A. degrees at the University of California at Los Angeles. He is a member of the State Bar of California and serves on editorial board of its International Law Journal.